Mary Jackson had always been part of the family.

That's all I knew.

"Aunt Mary" was different than the rest of my aunts, both my mom's five sisters and the close family friends kids call aunt to highlight that connection.

She was in her 90s, dark complected and had a southern lilt to her voice left behind from growing up in Virginia.

I didn't really think much of the history of the relationship or how this woman with the big hugs came to be part of the family. I certainly didn't think about her history growing up as a black woman at the turn of the century.

That was until February of seventh grade.

The acknowledgment of Black History Month was less than a decade old, and probably younger in my part of world in Margate. Diversity was neither a reality nor a discussion in the mid-1980s.

Here I was, 12 years old, learning about this history from books.

I don't remember if I asked or my mom suggested it. But when it was time to write a report about what we had learned, I decided to do a little extra by interviewing Aunt Mary, who was then approaching her 101st birthday.

Who else would know more about black history than she?

So my first interview was on my grandmother's green, push-button landline, as Aunt Mary happily answered questions from her Atlantic City home.

Mary Jackson was born July 14, 1884, in Staunton, Va.

She left school midway through eighth grade, but she continued to learn.

Working as a housekeeper, whenever she heard words she didn't know, she would write it down and then look them all up in the dictionary later.

Aunt Mary explained that she never recognized or accepted prejudice. She met those encounters instead with humor and an attempt, it seemed, at education.

One time, she went to a movie and sat in the middle of the theater. Blacks were relegated to the balcony at that time, so it did not take long for an usher to come and tell her to move.

"Why?" she asked.

"Because this section is reserved for whites," he replied.

"Well, who told you I'm not white?" she shot back, staying seated.

The usher returned with a police officer.

"If you can go out and find the same quarter I gave you, I'll leave," she told him. "The quarters aren't fighting, so why should you?"

Another time, she was getting on a bus that seemed to have no open seats. Then she saw a man stretching himself across three or four seats to keep her from sitting there.

She stepped over one of his legs and sat down.

"The man jumped up real quick," she recalled. "The man driving had to stop because he was laughing so hard."

Aunt Mary married at 20. She and her husband would have three children, with the eldest living just 18 months.

"We live with what God gives us," she told me of her losses. "It's not always what we want, but we live with it.

Her mood lightened as she told me how, when she would push her baby boy in his pram, people would tell her he resembled Robert E. Lee.

This did not surprise her. Everyone in Staunton knew the Confederate general was her grandfather, she explained.

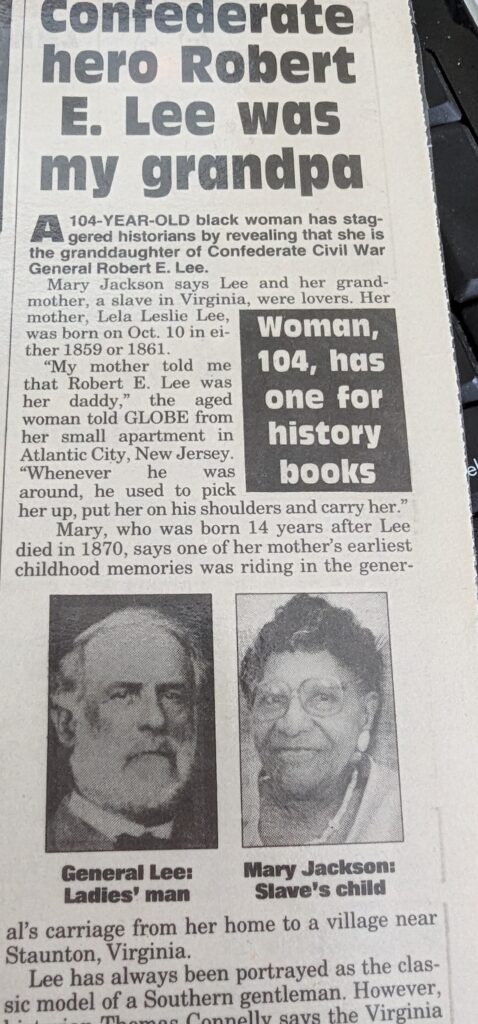

The "Globe" would write about Aunt Mary a few years later.

They told the story of how "a 104-year old black woman (had) staggered historians by revealing she is the granddaughter of Confederate Civil War General Robert E. Lee."

But the story differed from her telling to me.

The magazine said her mother was born of a relationship Lee had with a slave.

Her father was the son of slaves, she told me. Her mother, however, was the eldest of four children General Lee would have with young a Native American woman the soldier sent back to his sister after her mother was killed at Bull Run.

When he returned to his sister's, he saw this beautiful young girl singing in the field, Aunt Mary claimed.

"I knew that Mr. Lee stood for slavery," she told the "Globe," "But that didn't bother me none."

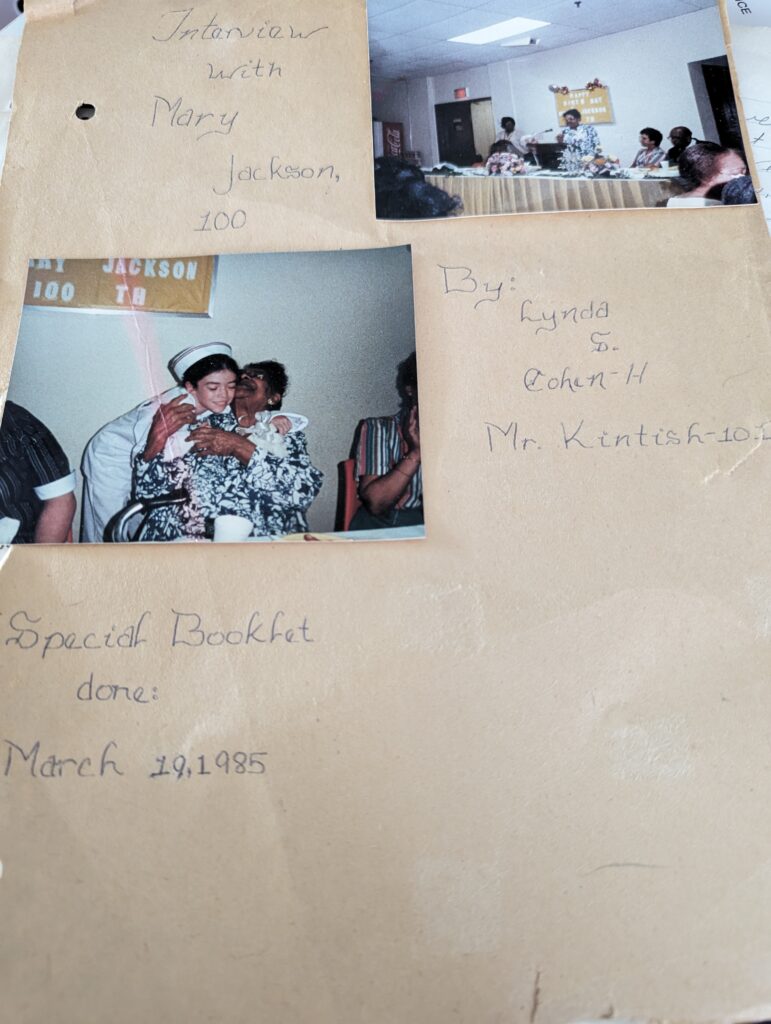

The year before my interview with Aunt Mary, there was a large celebration for her 100th birthday. Many people spoke about her, and I even performed a song and dance.

The highlight, of course, was Aunt Mary.

She stood up, addressing the crowd and pointing our various people throughout the room, easily recalling how they met or an anecdote about them.

"I know I don't need to stand up," she said. "But I'm showing you I can."

Standing up, it seems, was something Aunt Mary did her whole life.