His smile is what strikes you first.

It brightened young Micah Tennant’s face so much that some said it looked like he had a halo of light over him.

Then there’s the music. The 10-year-old Atlantic City boy enjoyed all types, singing along as his mother’s camera rolled.

He wanted to be a DJ like his uncle.

“How are you going to be famous if you don’t let me record you?” Angela Tennant would ask her youngest child.

Now those videos help the mom of three share her beloved “Dew” with people who never met him, even though they still mourn him.

He was caught in the crossfire of what the prosecutor called “petty vengeance” on a man who was sitting a bleacher away.

For five days, Dew’s body held on. He passed away that Nov. 20.

Now his mother is determined to keep his spirit alive by helping other young boys in the community.

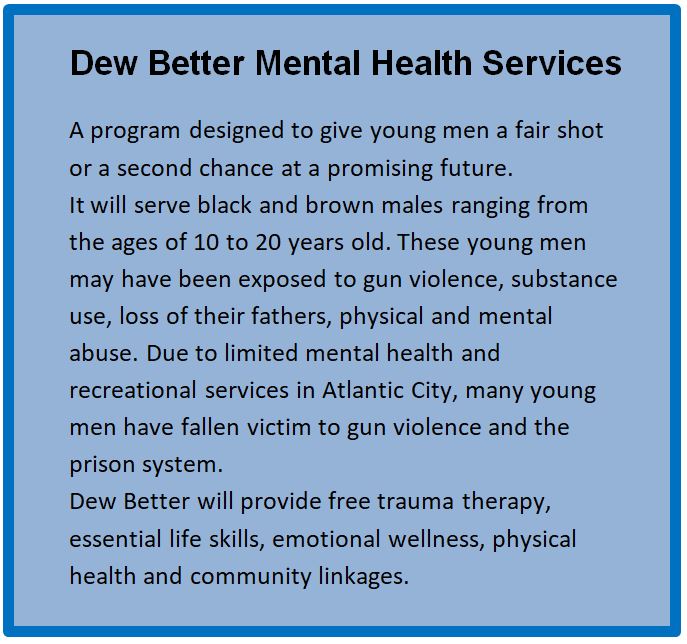

Dew Better Mental Health will give black and brown boys and young men ages 10 to 20 a place to come for help and mentorship.

“It’s a stigma in the black and brown community, not getting mental help, not getting therapy and things like that,” Angela Tennant says. “My son was a black boy. Whether people like to admit it or not, black and brown boys have the hardest time in America. So, yeah, that’s what I want to focus on.”

The violence on the streets often comes from tragedy many have lived. Angela's twins, Malachi and Machiah, lost their father when they were just 4. Taja'juan Russell was fatally shot in Atlantic City. Their maternal grandmother died 10 months after their little brother.

“I don’t want my son to be angry and feel like he’s got to go out and kill somebody because his brother got killed, or because his father got killed,” Angela says. “I want my son to be a productive citizen.”

He also will be part of a focus group for Dew Better.

His mother has already told him he and his friends will be recruited for a test run of the project.

Angela knows it’s a tough sell for a community that often can’t find or won’t seek help for fear of what people will think.

She had to convince her twins, freshman at Egg Harbor Township High School, when she sent them for counseling.

“It doesn’t mean that you’re crazy, it just means you don’t know how to express yourself. You don’t know how to express what you’re going through,” she explained. “You need somebody to guide you through that.”

Angela and her cousin Erica plan to officially roll out their project Sept. 9, on what would have been Dew’s 13th birthday.

Until then, they are still looking for a place in Atlantic City to house Dew Better, and welcome anyone who wants to contribute to the nonprofit’s funds.

“You can tell a kid you love them all day, but you have to show them that you love them,” Angela says.

“We want to create opportunities that provide an environment that’s a safe haven for them,” Erica says.

It was Erica who never left Angela’s side as Dew clung to life.

“Never in a million years would we have thought this could happen to us, until it happened,” Erica says.

“I think about Dew a lot,” his mother says. “I don’t think about the tragedy a lot. It’s just easier to cope with.”

She knows she will have to share those ugly parts with the kids she hopes to help.

“I want them to see what it looks like,” Angela says as she goes through pictures of her son in his hospital bed.

There is no mega-watt smile or twinkling eyes. A machine is doing his breathing for him.

It’s not how she wants him remembered, but it’s what she knows those who could be lost to the streets need to see.

“You don’t just ruin the life of the person you’re going after, you ruin your own life, you ruin your family’s lives,” she says.

In this case, an innocent life was lost.

There were so many people at the game that day, Angela made sure Dew and his sister were close. He was just five feet from her.

“You hear the first shot, and then it like stopped,” she recalls. “Then there were multiple shots.”

Everyone started to scatter. Her daughter was in front of her. She pushed the girl, telling her to run. Then she looked to Dew.

“He’s just sitting in the bleachers with his hands in his pockets. His eyes were open.”

She thought he was already gone, but saw him breathing. She placed him on the platform, telling him to stay focused, to stay with her.

“He tried to say mom,” Angela recalls.

She didn’t know at the time that he had been struck in the neck. No words would come.

“He just mouthed it,” she says.

That’s when the blood came. “I just freaked out.”

She would later learn that just to the side of them was the target of the shooting, retaliation for a gunfight three weeks earlier.

“I feel like, if you’re so gangster, why would you come anywhere public to kill anyone?” Angela asks.

She’s not saying killing is right, but asks, “Why would you go somewhere with thousands of people? It could have been anybody’s son.”

It’s the same question the prosecutor in the case had at the alleged killer’s detention hearing.

He could have waited until his target was alone, Levy said, but instead the accused “pointed his gun and fired away.”

“At the end of the day, when you kill someone, yes, they grieve the loss of the person,” Angela says. “But your family grieves the loss of you because you’re either going to go to jail or you’re going to get killed.”

Even if they are not brought to justice, her faith tells her there will be consequences.

“You also have to answer to God on Judgment Day.”

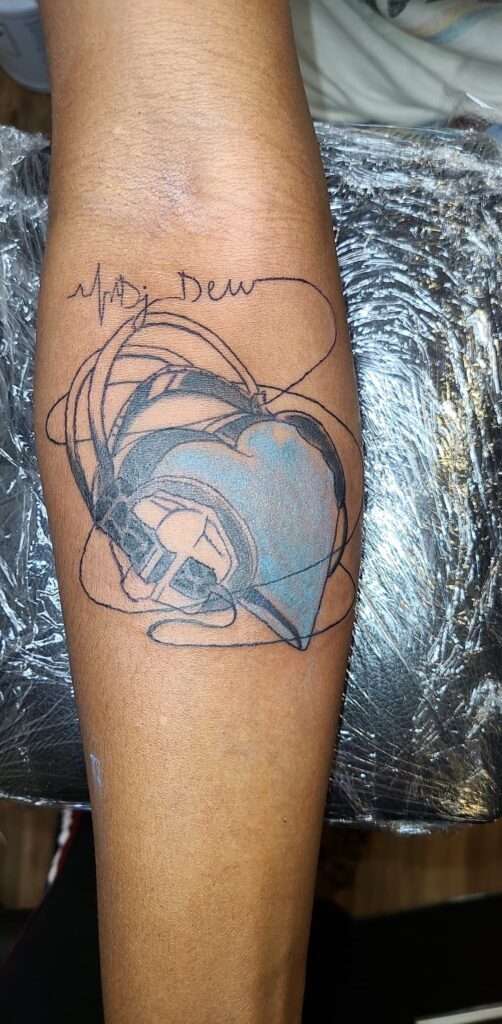

Angela Tennant has two tattoos honoring her son. The one on left was designed by Shameek Lynn.

“Her strength is at an all-time high,” friend Sakiyah Quick said. “I’m not sure how she does it, but her faith and mercy keeps her going. I wish I was half the woman she was when it comes to being strong. But that’s my sister and she’s teaching me.”

It was faith that kept Angela’s spirits up as she sat by her son’s bedside.

“I know the nurses at the hospital probably thought I was crazy,” she says of her positive attitude.

“There was nothing that they could say to me,” she says. “Of course, medically, they know. But spiritually, I know.

“If Jesus can turn water into wine, what can’t he do?” she asks. “He took two fish and five loaves of bread to feed the multitudes. Who wouldn’t have faith in that?”

Now, the grieving mom is hoping to turn her tragedy into triumph for her community’s young men and boys.

Like her favorite gospel song, “The Potter’s House":

You who are broken, stop by the potter's house You who need mending, stop by the potter's house Give Him the fragments of your broken life My friend, the potter wants to put you back together again Oh, the potter wants to put you back together again …

“A lot of people think I’m the strongest person in the world,” she says. “That’s not the case. I just still have two children that I have to care for because, if I could run away today or tomorrow and never come back, trust me, I would.”

So she stays and looks to heal her community while nursing her own broken heart.

“I wish we could all come together when it’s not a tragedy,” Dew’s mom says. “It’s sad that it takes something so tragic for everybody to come together. We should be doing it often, because these kids need us most.”

Anyone wishing to contribute to Dew Better can make donations directly to the nonprofits account at OceanFirst Bank, account number 74001020283.

Those who want to help can also email dewbetterclothing@gmail.com.